Exploring Ukraine’s Culture of Classical Music

Vladimir Putin and his supporters are engaged in a war to erase Ukraine and Ukrainian culture from history. Here, I dig into what exactly is Ukrainian culture by looking at its classical music history.

Vladimir Putin and his supporters are engaged in a war to erase Ukraine and Ukrainian culture from history. A state-supported Russian newspaper, RIA Novosti, just published an article where one can read that “Ukrainianism is an artificial anti-Russian construct that has no civilizational substance of its own, a subordinate element of an extraneous and alien civilisation” and that “the re-education of Ukraine could take a generation” as “besides the highest ranks, a significant number of common people are also guilty of being passive Nazis and Nazi accomplices. [...] Even the name Ukraine must be erased.” With this type of ultra violent language and reasoning, it is vital that we learn about Ukraine’s true history and culture, and tell others about it. Here, I occupy myself primarily with its musical culture, in the first of a series of articles I am writing which means to introduce the reader to important elements of Ukrainian history, and to two of its most important names in poetry and music, Taras Shevchenko and Mykola Lysenko.

Ukraine, now the center of our collective attention due to Russia’s cruel invasion, and Europe’s largest country without counting Russia, has a richer musical tradition than most realize. Because of Ukraine’s complicated history and oft-changing political situations, attributing a purely Ukrainian name tag to the many musicians born in its lands or with Ukrainian family origins is a difficult exercise, made even more difficult by the fact that Ukraine was for a long time dominated by the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union. Success for its artists often meant moving to Saint-Petersburg and Moscow, or to Europe and beyond to make a name for themselves. The lines are therefore often very blurry, yet Ukraine has a genuine musical voice.

Would you believe that Tchaikovsky (whose house in Ukraine was recently destroyed in the war), Stravinsky, and Prokofiev (who was born in Eastern Ukraine), all had deep Ukrainian roots? World-famous pianists Vladimir Horowitz, Sviatoslav Richter, and violinists David Oistrakh and Leonid Kogan were all born in Ukraine too. While not the subject of this introductory article, I will return to these famous names in the future. What is immediately clear from this, however, is that we know little about Ukraine’s musical story. Not only has this surprising country been fertile ground as the breadbasket of Europe, but it has also been propitious for the arts.

Unfortunately, international recognition of Ukraine’s contribution to the arts and particularly to classical music has not been taken seriously by Western musicians and music institutions, and other than Russia’s famous composers with Ukrainian origins cited earlier, people in the West know little or nothing about Ukraine’s music. That was embarrassingly my case as well until recent events led me to do some research. In fact, Ukraine’s musical culture is so vast that I could not do it justice in a single article. I will therefore do my best to share with you here, and in follow-up articles, the fruits of my digging along with my personal reflections on the classical music tradition of Ukraine.

As we all witnessed, in the early dawn of February 24, 2022, Russian tanks and troops crossed into Ukraine while Russian bombs began to fall on military and civilian targets across the country, in an onslaught which has not relented to this day. Since then, untold thousands of innocent civilians along with thousands of military on both sides have been killed, while many more have been injured, raped, maimed, tortured and abused in unthinkable ways, children included. Millions have had their homes destroyed and lives shattered. In six weeks’ time, nearly ten million people have left their houses and apartments, becoming refugees in their own country and beyond. Russia’s “president”, the inhumane and callous war criminal (how can it not be said?) Vladimir Putin, assumed that the Ukrainian people would welcome Russian troops with open arms and that the Ukrainian army would collapse overnight. What he did not understand about the Ukrainian people was their deep attachment to their land, to their unique culture, to their language, and to their hard-earned independence and democratic aspirations.

The sad truth is, Putin was not the only one to misunderstand Ukraine and miscalculate the reaction Ukrainians would have to his invasion. Most of us in the West truly had very little sense of Ukraine’s history and culture, partly making the same assumption Putin did: that Ukraine was an extension of Russia in both historical and cultural terms. In our defense, we assumed this because Ukraine was a core member state of the USSR and before that, a part of the Russian Empire; we didn’t dig further than that. The complex reality is that due to its strategic location at the crossroads of Eastern Europe, Belarus, Russia, the Caucasus, and the Black Sea, Ukraine has been the target of conquests since the Scythian tribes first rode in from the central Asian steppes in the 7th century BC. Ukraine’s history is fascinating, but marked by constant violence, conquest, genocide, migration, relocation, destruction, partition, and frequent instability.

Importantly, Russia’s domineering role in Ukrainian history has not been exclusive: Polish, Lithuanian, Austrian, Hungarian, Viking, Tatar, Mongol, Cossack, German, Turkish and even Persian armies have trampled through Ukraine’s endless plains. Like any large country, its people are made up of many ethnic groups who have mixed and come together over time; Ukraine is even more unique due to the opposing forces of its dominant religious groups, the (mostly Polish) Catholics in the West and the (mostly Russian) Orthodox Christians in the East, alongside plenty of Jews (for a long time Ukraine was home to one third of Europe’s Jewish population) and even Muslims. Ukraine has always been a crossroads where many cultures have collided and connected. It is not surprising then that the meaning of the word Ukraine itself is the “borderlands”.

Russia’s past is deeply tied to Ukrainian history, although it could be said that it was Ukraine that gave birth to Russia. The rise of Kievan Rus in the 10th century and the rule of Vladimir the Great (980-1015), of the Swedish Viking Rurik dynasty (which ruled what became Russia until 1598), are considered to be the founding blocks of Russian history. While there quickly grew to be multiple Rus principalities, including a powerful one based in Novgorod, it took over five hundred years for the Grand (Rus) Duchy of Moscow to unite all the Russian principalities and create the Russian Empire under its first Tsar, Ivan the Terrible, in 1547. It would thus indeed seem as though Ukraine and Russia share the same founders, but that their descendents split into different groups. The Kievan Rus principality was eventually defeated by the Mongols and Tatars in the 13th century, in one of the many twists and turns of Ukrainian history.

Putin is said to have been studying Russian history in recent years. Yet his approach has clearly been to handpick convenient aspects of history to found his arguments of invasion. If all great nations were to do the same, Great Britain would legitimately be able to reclaim the United States, France would reclaim Germany (or vice-versa since Charlemagne ruled both France and Germany as one), and the Italians would rightfully be able to claim most of Europe and North Africa. What a mess we would be in.

These arguments and broad territorial claims are evidently ridiculous. What we ought to recognize is a people’s will and a people’s culture, and the Ukrainians have aspired to independence for centuries, repeatedly voting for statehood with full rights since 1917 when the short-lived independent Ukrainian People's Republic was proclaimed. The path it has taken toward modern democracy and Europeanization wanted by the majority of its people since it regained its independence in 1991 after the fall of the Soviet Union is evidently incompatible with Putin’s concept of Russian power. What will ensue in the coming years is being played out right now in this terrible war.

Yet, Ukraine and Ukrainian culture exist! And we must all take some care to learn about Ukraine, and to acknowledge and recognize its culture. This recognition is precisely what Putin does not want the world to do, as he wishes to erase anything intrinsically Ukrainian with Russian culture and language. Thus learning about Ukrainian culture is itself an act of defiance toward this unspeakable aggression.

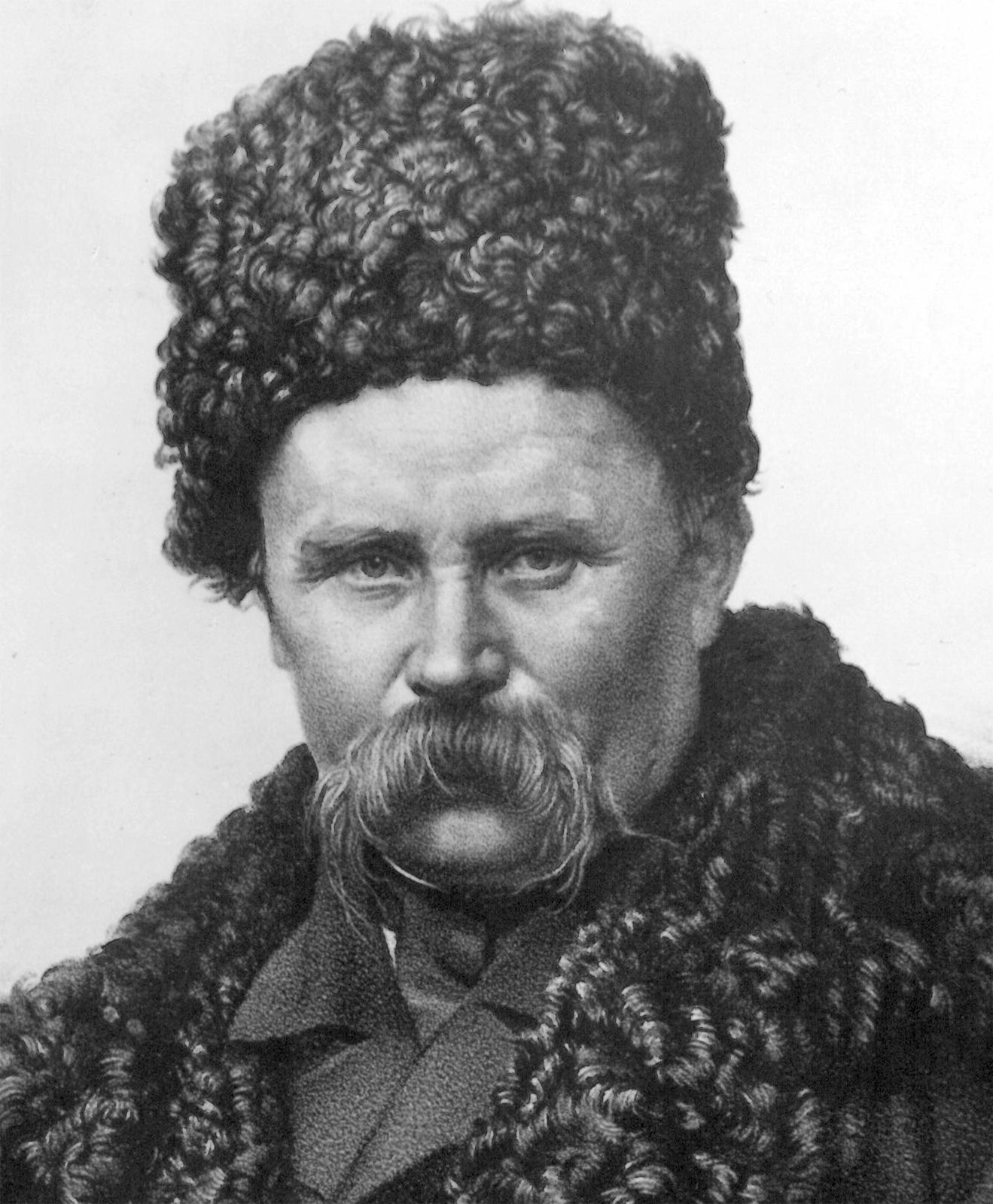

To understand contemporary Ukrainian culture and identity, you must know about the great artist and poet Taras Shevchenko, who has become Ukraine’s national conscience and inspiration. His influence has been constant over Ukrainian arts and politics ever since he first rose to fame in the mid 19th century.

Taras Shevchenko was born a serf (a peasant slave in the old Russian imperial system) in central Ukraine in 1814. He wrote exclusively in Ukrainian, a derivative of Ruthenian, an East Slavic language that shares its origins with Russian but has evolved independently over many centuries (Russians call it, somewhat disdainfully, “Little Russian” or “peasant Russian”). It is very important to note that speaking and writing in Ukrainian has often been considered subversive, as it was banned from the educational and administrative systems and from common use by both the Polish and Russian occupiers at various times in Ukrainian history, although it was somewhat tolerated during the Soviet era.

Thus the use of Ukrainian in print, by a former serf no less, was itself a major act of defiance toward the imperial Russian system, especially if we consider that the first book ever to be published in Ukrainian dates only from 1798, not because the language did not exist (Ukrainian can be traced to the 10th century), but because it was prohibited. It comes as no surprise then that one of Vladimir Putin’s main arguments for his invasion of Ukraine is to protect the rights of ethnic Russians living in Ukraine to continue speaking Russian without discrimination, which is of course twisted reasoning. Most Ukrainians speak Russian due to the many centuries of forced russification, and while Ukrainian has been re-established as the primary administrative language of the country, Russian is widely spoken across Ukraine. Even its president, Volodymyr Zelensky, is a native Russian speaker and only began to use Ukrainian regularly once he entered politics in 2019! In fact, he always defended the rights of Russian speakers and artists working in Ukraine to be free to use Russian like him (before entering politics, Zelensky was an actor whose films and stage shows were almost exclusively in Russian). Therefore, Putin’s reasoning on this count seems, like his other reasons (Ukraine is a Nazi country??) far-fetched, especially with Zelensky as president…

Taras Shevchenko was also an extraordinary artist who spent many years drawing and painting, leaving behind hundreds of masterworks. In fact, his artistic talent led him to gain early recognition amongst an educated class in Saint-Petersburg, where he went as a young man attending to his master. A group of Ukrainian and Russian intellectuals who recognized his artistic genius decided to pool together to purchase his freedom. Shevchenko thus left the chains of servitude at the age of twenty-four.

His first book of poetry was published in 1840, and in 1841 he published his most famous book of poetry, titled simply “Kobzar”, which means “bard” in Ukrainian, leading him to become known as Kobzar Taras. But in 1847 he was arrested and condemned to exile for having promoted Ukrainian independence, for having written in the Ukrainian language, and for having mocked Tsar Nicholas I and his wife the Tsarina Alexandra Fedorovna in his poem “The Dream”. He was sent to Orenburg in the Ural mountains as a private in the military, and the Tsar personally forbade him from drawing or writing anything. His forced military service lasted ten years, after which he eventually returned, weakened, to Ukraine before being exiled again on new charges of blasphemy. Shevchenko was then ordered to live in Saint-Petersburg, where he died, exhausted and sick, in 1861, at only 47 years of age and only 7 days before serfdom was wholly abolished by the new Tsar Alexander II across the Russian Empire. He had only lived as a free man for a dozen years over his entire life.

Kobzar Taras’ use of the Ukrainian language along with his nationalist political thinking, and defense of Ukraine’s peasant and working classes heavily influenced and encouraged subsequent authors, political thinkers, and artists. But his poetry also inspired many musicians, who set his texts to music, both in the Kobzar (bard) tradition, as well as in classical art song and choral settings. Shevchenko’s work helped to define the national consciousness of Ukraine and spurred a whole artistic and intellectual movement which was not ashamed to proclaim its Ukrainian identity. To this day, most Ukrainians know and recite some of his poetry, and countless monuments to Shevchenko dot Ukraine as well as many cities beyond its borders, throughout the wide Ukrainian diaspora, including Washington D.C. (his monument was inaugurated by President Eisenhower) and Paris.

Ukrainian Kobzars usually accompany their poetry and songs on traditional instruments such as the bandura or the kobza. Here is an example of a traditional Ukrainian bard from a rare 1936 film (scroll to middle of the video to see and hear this special music to give you an idea of kobzar culture):

Although he was initially buried in Saint-Petersburg, Shevchenko’s wish to be buried in Ukraine was honored two months later, in a project organized by his friends and supporters. It so happens that one of his pallbearers in Ukraine was an ardent admirer of Shevchenko, the young musician Mykola Lysenko.

Lysenko (1842-1912), although born into a wealthy aristocratic Ukrainian-Cossack family with glorious ancestors, was always passionate about music and especially the traditional peasant folk music of his Poltava region, by the Dnieper River. He was lucky to be able to meet and spend a lot of time with the famous blind kobzar, Ostap Veresai (1803-1890), whose music Lysenko transcribed and studied. Lysenko, a talented classically trained pianist, composer and choral conductor who even studied for several years in Leipzig (where Bach, Schumann and Mendelssohn had all lived and worked) and in Saint-Petersburg with Rimsky-Korsakov and Modest Mussorgsky, was so interested in kobzar music that he traveled around Ukraine in search of all the folk musicians he could find, studying and transcribing hundreds of songs and epics (called “dumas” or “dumi”). He wrote several articles and books on the subject, and is considered an early ethnomusicologist for this very serious and important work which is studied to this day.

This led him to develop a unique aesthetic as a composer writing music in classical form, but incorporating the sounds of this traditional kobzar music into his compositions. In addition to that, he set to music many Ukrainian songs and poems, including many by Shevchenko. He also wrote operas on historical Ukrainian subjects, his most famous being “Taras Bulba”, an opera based on a work of the same name by Nikolaï Gogol (another famous “Russian” with Ukrainian roots) treating a fictional historical subject about a fight for freedom by the Cossacks against their Polish occupiers in the 17th century. Tchaikovsky was so impressed by Lysenko’s Taras Bulba that he tried to convince him to have the libretto translated into Russian and performed in Saint-Petersburg. But Lysenko, attached as he was to the Ukrainian language, refused, and his opera was never performed during his lifetime (the premiere took place in 1924 in Kharkiv).

As a result of his search for an authentic Ukrainian sound, Mykola Lysenko is considered to be the father of the Ukrainian nationalist music movement, in a vein similar to other nationalist composers like Grieg in Norway, Smetana and Dvoràk in the Czech Republic, Russian composers of the period like Mussorgsky, Glinka and Rimsky-Korsakov, Sibelius in Finland, Albeniz, Granados and de Falla in Spain, Elgar in Britain and plenty of others at the turn of the century. Unfortunately, difficulty getting his work out due to the Russian censorship of the Ukrainian language and other factors made it difficult for Lysenko’s reputation to grow outside of Ukraine. His influence, made even greater after he founded the Lysenko Music School in 1899 in Kyiv, gave rise to a whole slew of disciples who helped turn Ukraine into a very active center for music in the 20th century, such as Stanyslav Lyudkevych, Kyrylo Stetsenko, Yakiv Stepovy, and Mykola Leontovych (particularly famous as the composer of “Carol of the Bells”).

Lysenko wrote many art songs, choral pieces (including the unofficial Ukrainian anthem, “Prayer for Ukraine”), operas and hundreds of beautiful pieces for piano, which I have begun to explore and play. To conclude this introductory article about Ukrainian music, I share with you my performance of Lysenko’s “Funeral March” in memory of Taras Shevchenko, which I personally dedicate to the heroes and to the countless victims of this terrible, inhumane and grotesque war in Ukraine.

Lysenko’s Funeral March in memory of Taras Shevchenko

Ukraine’s musical culture, heavily influenced by its traditional folk music, is therefore truly unique. Straddling Eastern and Western cultures, it has benefitted (and suffered) from the influences of Europe’s classical culture, Russia’s greatness in music and literature, and from the influx of Black Sea civilisations all the way to the Ottoman Empire and present-day Turkey. To find their voice, Ukrainians have had to fight to use their own language like Taras Shevchenko, and to seek out its roving kobzars who carried the immemorial stories and songs of their land with them, like Ostap Veresai, whose oral tradition was put to paper by Mykola Lysenko.

While many Ukrainian composers have produced great work before the 19th century, they typically found their way to Europe or Russia to make their careers, trying to blend in with more dominant cultures to make a living. In my next articles, I will continue to explore Ukraine’s musical history and memorable musicians, from the 16th century all the way to our day. But if there is one Ukrainian composer you must know, it is certainly Mykola Lysenko, and I hope you will begin to explore his music on YouTube and other streaming services where you can listen to recordings of his works, even if the number of good albums is unfortunately limited. I do hope more musicians will begin to perform and record his wonderful works.

Some further resources and information about Taras Shevchenko and Mykola Lysenko follow here, including a playlist I am making on YouTube about Ukrainian culture and music that includes my selections of works mentioned here as well as others I think make worthwhile listening.

If you have any comments or questions, I will be happy to receive them. Thank you for reading.

Links

https://taras-shevchenko.storinka.org/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taras_Shevchenko#Poetic_works