Bach, always. But what about Couperin?

An inquiry into the ills of incomplete narratives in classical music -

J.S. Bach (1685-1750) is widely considered to have been the greatest musician to ever live. While it is true that Bach was a unique composer of extreme genius, whom I love deeply and whose music I play frequently, his post-mortem glory obfuscates the talent and genius of other extremely important composers of his time-period deserving of our esteem and attention even today.

This is particularly true of François Couperin (1668-1733), one of France’s greatest musicians whose reputation today is unfortunately far below that of Bach’s.

Many reasons are to blame for this, but there is no excuse today to let so much great music sit by the wayside, when the Internet makes finding and listening to music so easy. I would even argue that we have a duty to present a more precise and fair view of music history to include the “lost composers and musicians” whose social standing, network, net worth, political and public-relations know-how, or post-mortem reputations suffered from unjust biases or bad luck. This is not only true of Couperin but of many of his and Bach’s peers, not limited to but also including women, mixed-race, black, and Jewish composers.

There is indeed much to be done to bring meritorious musicians to the public’s attention and try to establish a more equanimous perspective on the history of classical music. What we have been taught by mainstream concert programming and general music education, almost unchanged for a century and overly guided by politics, culture wars and past mindsets, cannot stand still in our time.

The shade inadvertently brought about by Bach and a slew of other dominant composers, such as Handel, over Couperin and many other extraordinary musicians results in part from a primarily 19th century German-centric and anti-French narrative which has kept much beautiful and important music out of the great concert and opera halls of the world, to the public’s detriment.

Italian baroque and classical composers did not suffer as much as their French counterparts from being forgotten in large part because Italy as a nation-state was inexistent until the late 19th century and never posed a threat to the growing power of Germany. And England, like France, has been a nation state for more centuries than most other European countries and did not need to engage in a cultural war with France to forge its national identity, unlike the German-speaking world whose challenge was to find commonalities, such as an enemy on its border to develop its political projects.

The French Revolution was also a major disruption in cultural history similar to what happened at a later time with the Russian Revolution for all pre-U.S.S.R. culture or with Chairman Mao's Cultural Revolution in China. This partly explains 19th century French musicians’ own lack of interest in 17th and 18th century French music, as the page had been turned.

After a century and a half of French cultural and military preeminence from the days of the Sun King’s court in Versailles through the entire Age of Enlightenment, the German-speaking worlds consciously took advantage of France’s political weakness and internal discord to establish their own cultural mythology, exalting their medieval legends and giving rise to German romanticism. This resulted in a newly found sense of cultural hegemony in a land of countless independent and rival principalities, helping to crystalize a united consciousness for Germany’s future nation-state.

At the same time, European elites were being influenced by forceful (and truly great) composers and cultural influencers such as Beethoven, E.T.A. Hoffman, Weber, Mendelssohn, Schumann, Liszt and later Wagner. Music that was German or German-influenced was considered “serious music”, while French music was mainly relegated to, and often caricatured as effeminate, light entertainment for the salons and the music halls. Only French composers who espoused German esthetics could be taken seriously. This, of course, was a twisted portrayal, but it did help to create the modern myth of a formal German nation, culturally and historically united by its language, history, philosophy and music.

Otto von Bismarck, powerful chancellor of Prussia and of the German Empire to which he almost singlehandedly gave birth, understood this and took advantage of these emotions to unite German states behind the common cause of defending “the fatherland” against the enemy. France’s unadapted imperial forces capitulated in a matter of weeks in 1870, proving Bismarck’s calculations right, and thus sealing the unification of Germany once and for all, with its known consequences. The new German Empire and its new emperor Wilhelm I were actually proclaimed in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles (which Couperin would have walked through often)!

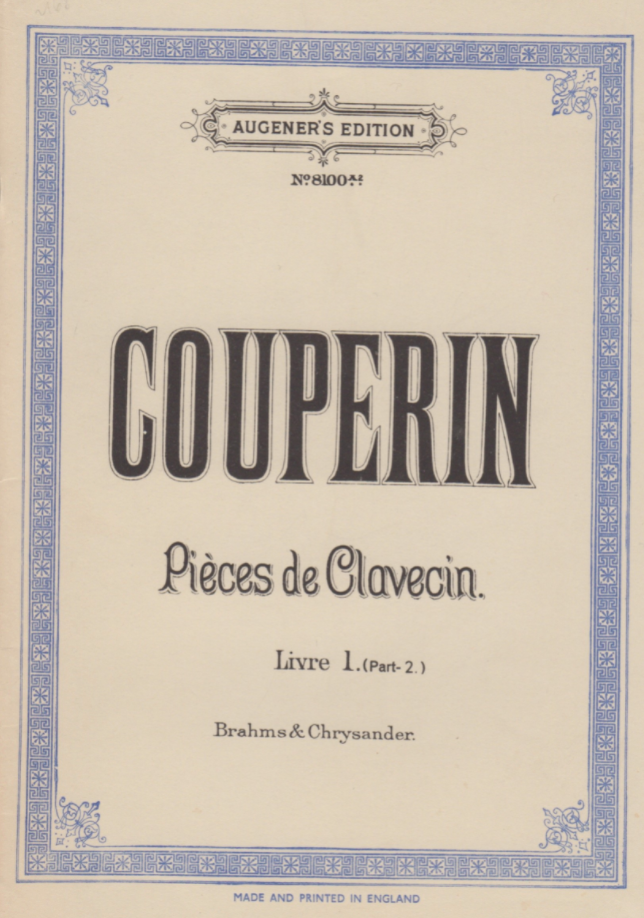

Ironically enough, however, it took a solidly German musician living in Vienna to bring Couperin back from obscurity by performing his music in public and editing a new edition of his works for publication in the 1880s.

Did you guess who it was? That's right!

Johannes Brahms himself.

In fact, he was so enthralled by the Baroque master that he incorporated some of his musical ideas into his late compositions. But Brahms was an enlightened musician who could see value wherever he found it. He even said that his favorite opera of all time was Bizet's Carmen, which was certainly not a patriotic choice!

In France, anti-German sentiment following the defeat of 1870 did also lead to renewed interest in the origins of “real” French music from a nationalistic lens, and both Couperin and Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683-1761) benefitted from these changing winds. For one, Claude Debussy (1862-1918), at first an avowed Wagnerian like most French musicians at the time, found much inspiration from these old masters’ music, as did Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) a few years later.

But with renewed attention given to the music came a fascination with the instruments of the Ancien Régime (the pre-revolutionary period of monarchy). They had, however, been stored away or left to rot: no more playable harpsichords, lutes, or viols. So toward the end of the 19th century the French piano company Pleyel (whose founder had been an Austrian pupil of Joseph Haydn’s…) began to experiment with modern harpsichord-making. These new takes on old instruments were meant to give a sense of how ancient music authentically sounded, but they were so different that they have themselves become historical curiosities.

Built more like pianos with heavy steel frames instead of wood, and intended to be louder than original harpsichords, they had little to do with their forebears. But they nonetheless opened the doors to the idea of period practice, and sparked young Wanda Landowska’s interest. Born in Warsaw in 1879, Landowska was a talented pianist who was to become almost exclusively a harpsichordist, to the dismay of her friends and fans. But the force of her personality along with the passion she exhibited for these sounds and this forgotten music secured her an essential place in the history of music.

The debate between contemporary performance styles on modern instruments of old music vs. authentic period practice on old instruments has been raging ever since the early 20th century. On this matter, Landowska is known for having once responded to criticism by the romantic Bach-playing cellist Pablo Casals, who accused her of going against the times, in these cutting terms: “You play Bach your way, and I will play Bach ‘his’ way.” Clever. But she was fighting an uphill battle for acceptance at that time and was right to put her foot down.

Her curiosity for this forgotten repertoire sent her scouring many libraries and collections in search of information, music and instruments of the period. Bach, Couperin, Rameau, Scarlatti and lesser known composers were her daily bread, something that was revolutionary in her day. She was also supportive of contemporary music and encouraged composers to write new music for the harpsichord, and many, such as Manuel de Falla and Francis Poulenc, obliged.

Of Jewish origins, she had to flee Europe in 1940, resettling in Connecticut until her death in 1959. Her impact cannot be underestimated for both Europe’s and America’s newly found interest in the baroque repertoire beginning in the 1950s, and we owe her a huge debt of gratitude for opening wide the doors to this treasured but forgotten repertoire.

After the war, several waves of researchers and musicians interested in this music arose and established early music scenes. Many impactful discoveries and recordings were made in the following decades. One important such musician was conductor Jean-François Paillard (1928-2013) who, along with his ensemble, recorded hundreds of never-before-heard baroque music in the 60s and 70s. He even popularized the famous Canon in D by Johann Pachelbel (1653-1706), which today is one of the most well-known baroque tunes people have heard. His albums at one time sold faster than all the Beatles' albums put together! Antonio Vivaldi’s Four Seasons is another example of an extremely popular baroque masterpiece, which was not known to the general public until the 1950s.

After a few decades of baroque music discovery on “normal” (i.e. modern) instruments, a new wave of specialized musicians and ensembles focusing on “period practice” arose in the 1970s and 80s. Their interest was in finding the true sound and style of early music, which led them to learn how to make, play and exploit traditional baroque instruments.

For example, instead of using violins with modern steel or nylon strings, they would change them to sheep’s gut, which is how it was done in the 18th century. They also began to tune their instruments to a lower frequency than the common "A 440", generally at "A 415" which sounds out of tune to modern ears, but was common practice in the 18th century (a subject worthy of its own article one day). These historically-minded musicians worked diligently to replicate as much as possible what Bach or Couperin experienced and heard in performance.

This research and performance practice work has been an invaluable addition to our understanding of the music of the past. Thousands of beautiful and informative recordings of known and completely unknown works have been made by period practice musicians over the last fifty years, giving listeners a treasure trove of new ‘old’ music to listen to, along with lots of new editions of works that had not been reedited, or in some cases ever published, since they were written.

However, this has also created its own unexpected problem: the extreme specialization of the genre, making it difficult to continue performing baroque music on modern instruments!

While it was standard practice before the 1980s to perform baroque music on today's instruments such as the piano, the movement toward “period practice” has been critical of playing early music on instruments that were not available to musicians in the composers’ time period. This has made traditional orchestras, chamber ensembles and individual musicians shy about playing baroque music with contemporary instruments, with the exception of standard fare Bach and occasional Handel and Vivaldi.

While I am myself an ardent supporter of period practice, I do not sanction the movement to excise early music repertoire from being performed on modern instruments, for two primary reasons: first, because it limits the number of people who will be exposed to some of the great works of the past as they may not be attending concerts by period practice specialists or listening to their recordings; second, because I believe that modern instruments can be wonderful allies in exhibiting qualities in early music not available to the mechanics, playing techniques and timbres of old instruments.

I am a pianist who adores the harpsichord, an instrument which I studied seriously in graduate school. But I believe that, just as we love hearing Bach performed on harpsichord as well as on piano, we should also hear Couperin’s music and that of other 17th and 18th century composers on both authentic and modern instruments. I know that this can sound wrong to purists, but there is musical value in doing so. The piano can, for example, bring out sonorities, contrasts and subtleties completely unavailable to the harpsichord, something I will demonstrate over time as I explore some of this repertoire on the piano.

Lastly, it is important to realize that in the 17th and 18th centuries, keyboard music was meant to be performed on many different types of harpsichords, clavichords, and even organs since nothing was standardized nor industrialized, and every instrument maker had his unique approach, creating an array of very individual keyboard instruments, with their own sounds and timbres. Couperin and Bach would have been used to playing on very different types of keyboard instruments and easily switching from one to another according to what they had at hand in any given place. Had they had modern pianos available to them, it would have been one more interesting option to them, which they could not have rejected.

I am, like the old keyboardists, an instrumental maximalist, focused on music’s inherent qualities whichever instrument it is I have at hand, in service of music.

In any case, the narrative we have been used to about classical music's grand figures reigning supreme and unchallenged at least since the late 19th century must change, not to the detriment of our beloved composers, but in the interest of a fair representation of music history and its many sidelined talents over the centuries. The case of some of France's greatest composers being near totally erased from traditional concert programming is particularly shocking, which is why I tried to understand and explain how that came to be in historical terms.

However, it goes to show that, for a multitude of reasons, some very worthwhile musicians and compositions have been forgotten when they should, in fact, be promoted and performed. The tireless work of researchers and musicians over the last century has brought many of those near the surface, but it takes time to change historical narratives which we so long took for granted. Today, the web and streaming music distribution make it really easy to learn about these composers of yore and listen to their music when available.

While the focus of this article has been to give readers some necessary context to explain my quest to bring less appreciated composers to their attention, I do plan to say more about specific composers in my next articles.

I will soon give a proper overview of the Couperin family, fascinating for the many musicians bearing the family name over a period of two hundred years, akin to the talented multi-generational Bach family.

I hope you will subscribe to this platform, to read and hear about my favorite forgotten composers, which I hope will enrich your musical tastes and listening pleasure.

Please comment on this article if you found it interesting or have questions!

Thank you for reading.

George Lepauw